Component

The word “component” is a hugely overloaded term in the software development industry but, in the C4 model, a component is a grouping of related functionality encapsulated behind a well-defined interface. If you’re using a language like Java or C#, the simplest way to think of a component is that it’s a collection of implementation classes behind an interface.

With the C4 model, components are not separately deployable units. Instead, it’s the container that’s the deployable unit. In other words, all components inside a container execute in the same process space. Aspects such as how components are packaged (e.g. one component vs many components per JAR file, DLL, shared library, etc) is an orthogonal concern.

Components vs code?

A component is a way to step up one level of abstraction from the code-level building blocks that you have in the programming language that you’re using. For example:

- Object-oriented programming languages (e.g. Java, C#, C++, etc): A component is made up of classes and interfaces.

- Procedural programming languages (e.g. C): A component could be made up of a number of C files in a particular directory.

- JavaScript: A component could be a JavaScript module, which is made up of a number of objects and functions.

- Functional programming languages: A component could be a module (a concept supported by languages such as F#, Haskell, etc), which is a logical grouping of related functions, types, etc.

If you’re using an object-oriented programming language, your components will be implemented using one or more classes. Let’s look at a quick example to better define what a component is in the context of some code.

The Spring PetClinic application is a sample codebase that illustrates how to build a Java web application using the Spring MVC framework. From a non-technical perspective, it’s a software system designed for an imaginary pet clinic that stores information about pets and their owners, visits made to the clinic, and the vets who work there. The system is only designed to be used by employees of the clinic. From a technical perspective, the Spring PetClinic system consists of a web application and a relational database schema.

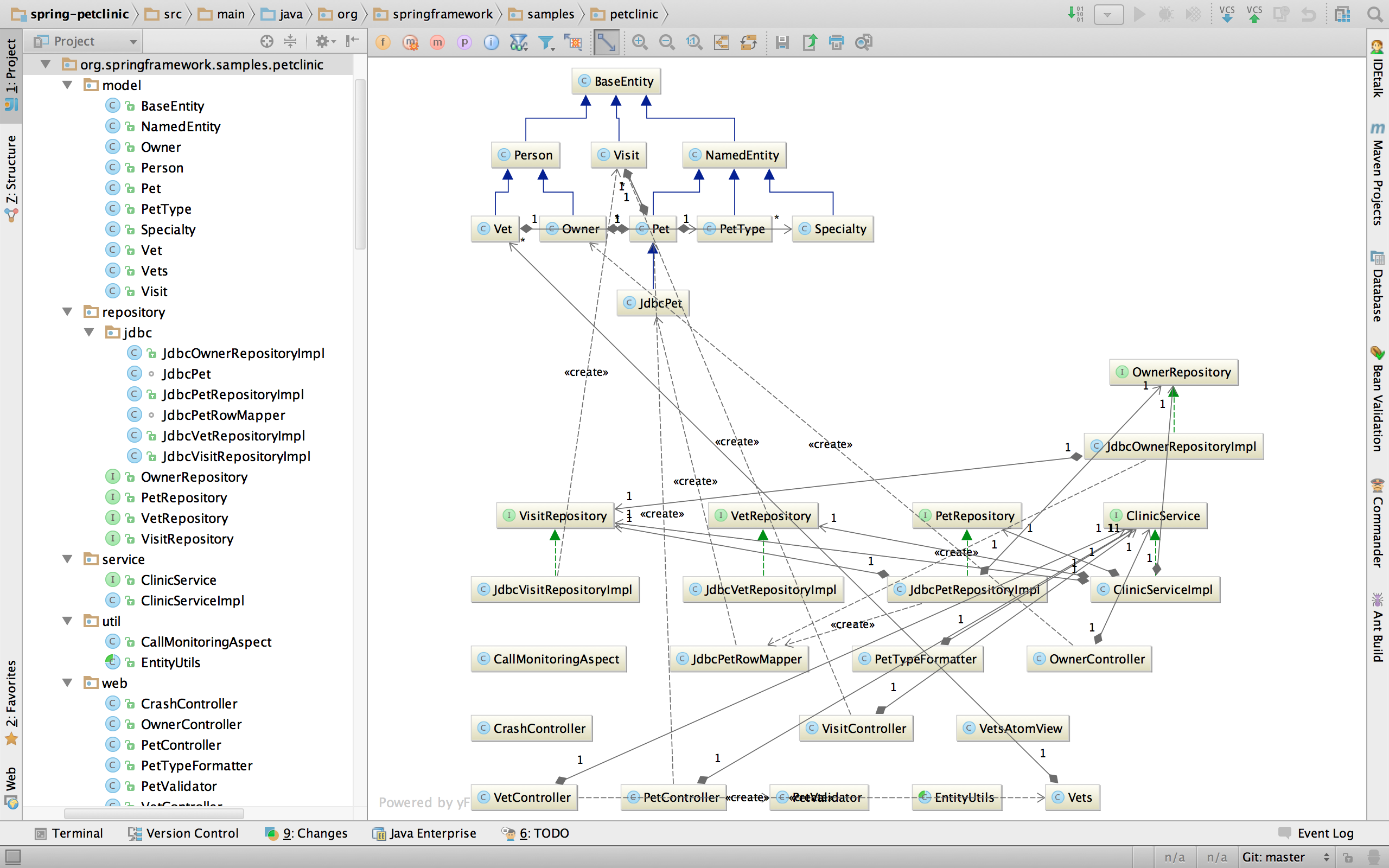

The version1 of the web application we’ll look at here is a typical layered architecture consisting of a number of web MVC controllers, a service containing “business logic” and some repositories for data access. There are also some domain and util classes too. If you download a copy of the GitHub repository2, open it in your IDE of choice and visualise it by reverse-engineering a UML class diagram from the code, you’ll get something like this.

As you would expect, this diagram is showing you all the Java classes and interfaces that make up the Spring PetClinic web application, plus all the relationships between them. The properties and methods are hidden on the diagram because they add too much noise to the picture. This isn’t a complex codebase by any stretch of the imagination but, by showing classes and interfaces, the diagram is showing too much detail.

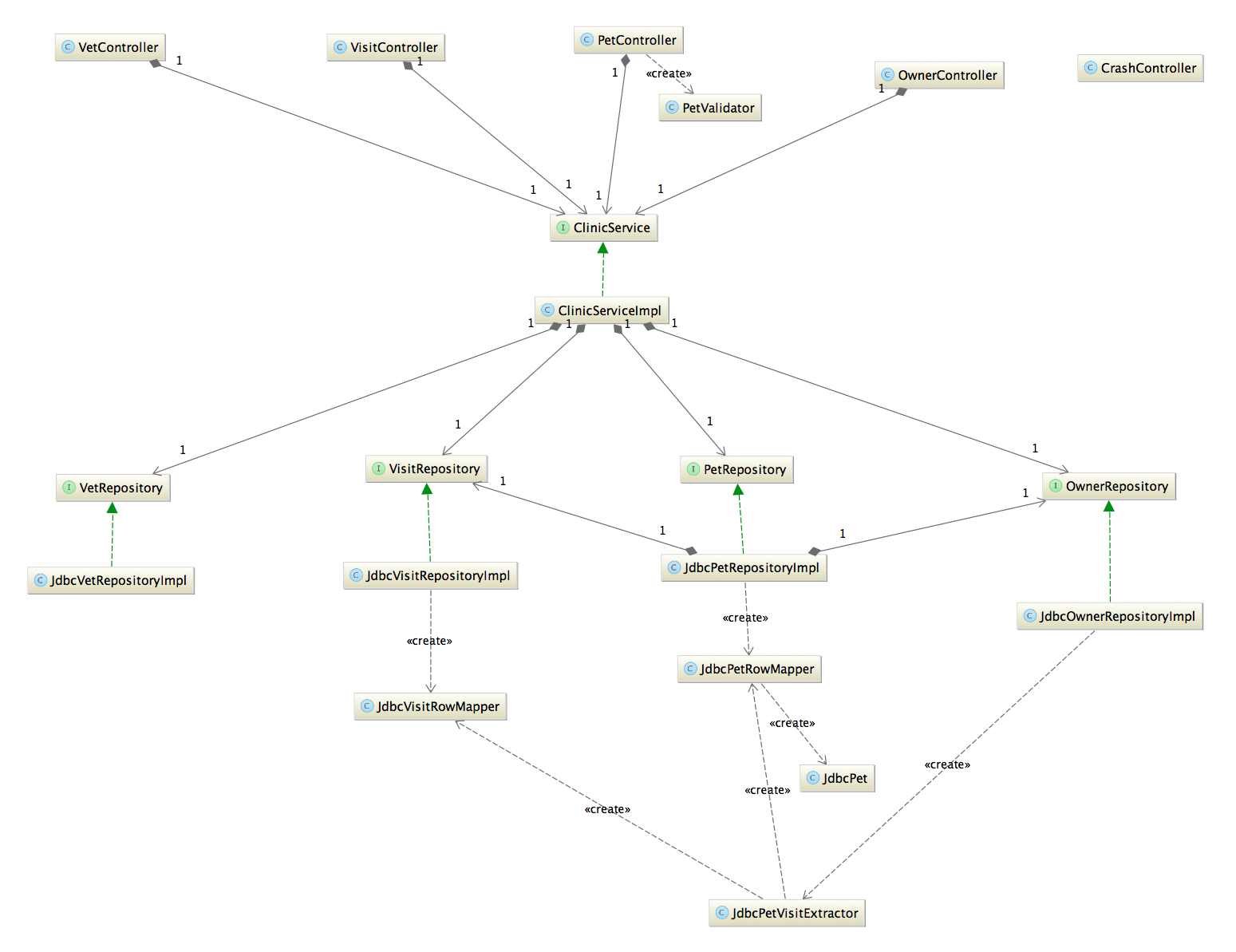

Let’s remove those classes that aren’t useful to having an “architecture” discussion about the system. In other words, let’s only show those classes/interfaces that have some significance from a static structure perspective. In concrete terms, for this specific codebase, it means excluding the model/domain classes (they are just data structures) and util classes.

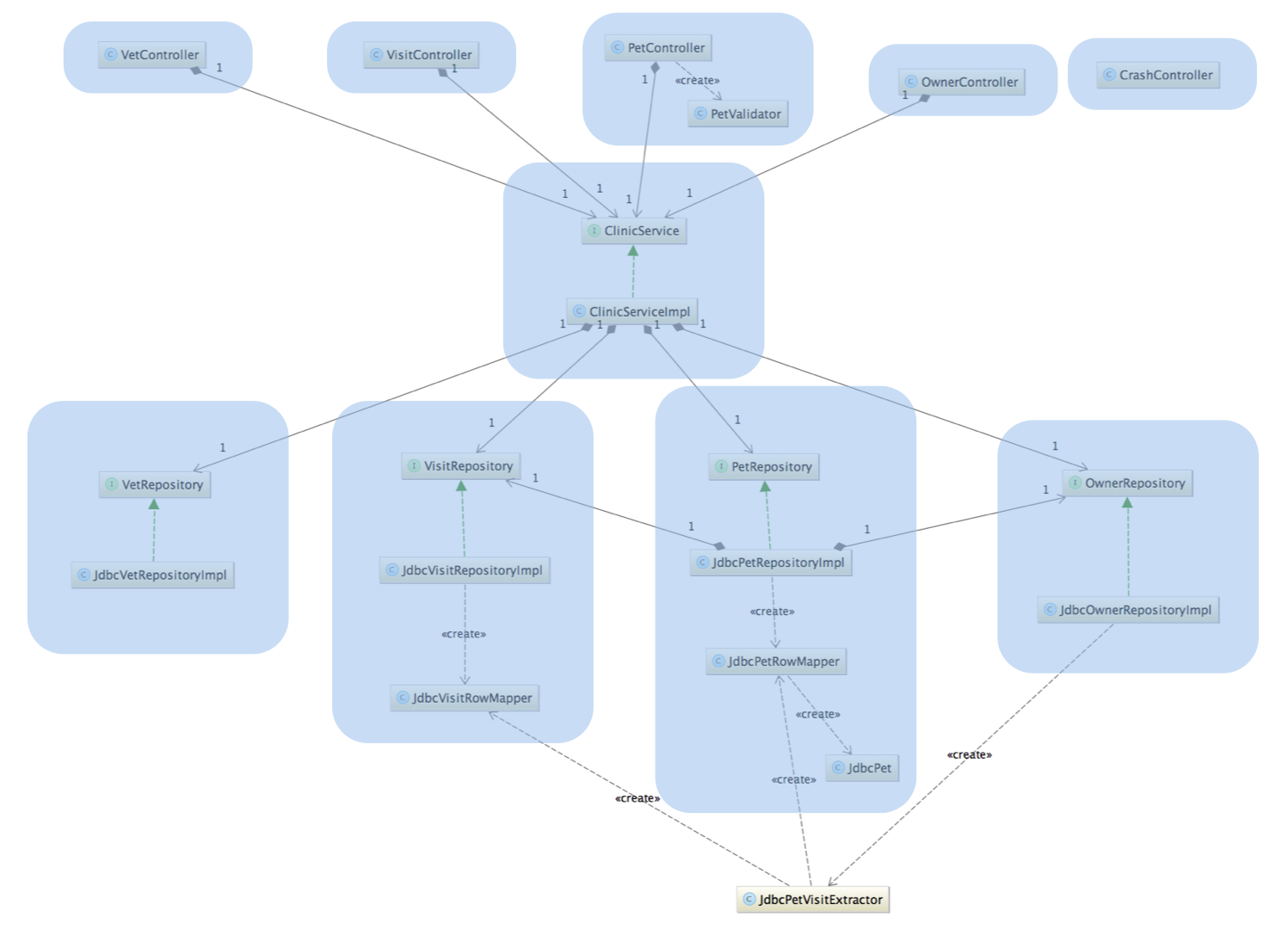

After a little rearranging, we now have a simpler diagram with which to reason about the software architecture. We can also see the architectural layers again (controllers, services and repositories). But this diagram is still showing code-level elements (i.e. classes and interfaces). In order to zoom up one level, we need to identify which of these code-level elements can be grouped together to form “components”. The strategy for grouping code-level elements into components will vary from codebase to codebase but, for this codebase, the strategy might look like this.

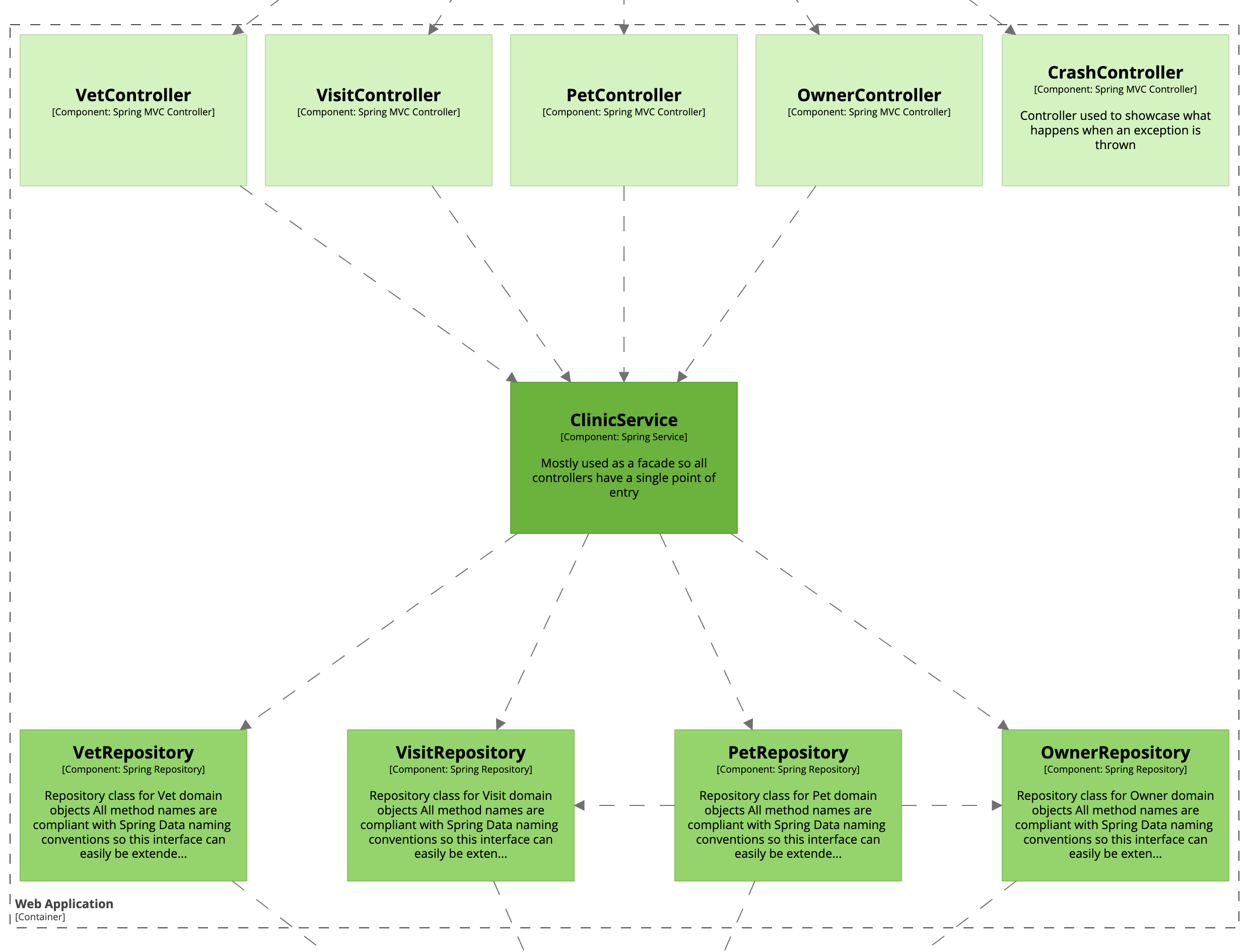

Each of the blue boxes represents a “component” in this codebase. In summary, each of the web controllers is a separate component, along with the result of combining the remaining interfaces and their implementation classes. If we remove the code level noise, we get a picture like this.

In essence, we’re grouping the classes and interfaces into components to form units of related functionality. You will likely have shared code (e.g. abstract base classes, supporting classes, helper classes, utility classes, etc) that are used across many components, such as the JdbcPetVisitExtractor in this example. Some can be refactored and moved “inside” a particular component, but some of them are inevitable.

Although this example illustrates a traditional layered architecture, the same principles are applicable regardless of how you package your code (e.g. by layer, feature or component) or the architectural style in use (e.g. layered, hexagonal, ports and adapters, etc). If your codebase is small enough, you can go through this process manually. For larger codebases though, you’ll likely want to consider automatic generation of component diagrams by reverse-engineering your codebase (example).

- 1 the diagrams shown here do not reflect the latest version of the Spring PetClinic, but are sufficient for the discussion

- 2

git checkout 95de1d9f8bf63560915331664b27a4a75ce1f1f6is the version these diagrams were based upon

FAQ

Is a Java JAR, C# assembly, DLL, module, package, namespace, folder etc a component?

Perhaps but, again, typically not. The C4 model is about showing the runtime units (containers) and how functionality is partitioned across them (components), rather than organisational units such as Java JAR files, C# assemblies, DLLs, modules, packages, namespaces or folder structures.

Of course, there may be a one-to-one mapping between these constructs and a component; e.g. if you’re building a hexagonal architecture, you may create a single Java JAR file or C# assembly per component. On the other hand, a single component might be implemented using code from a number of JAR files, which is typically what happens when you start to consider third-party frameworks/libraries, and how they become embedded in your codebase.